Memories of RBG

/Thursday, June 16th, Blue Ridge Center for Lifelong Learning will host Asheville resident, Stephen Wiesenfeld, as a guest speaker discussing his nearly 50-year relationship with Ruth Bader Ginsberg - first as her client in a landmark case she argued before the US Supreme Court in 1975 and later as her friend for the next 45 years.

Their story and details about registering for this event here …

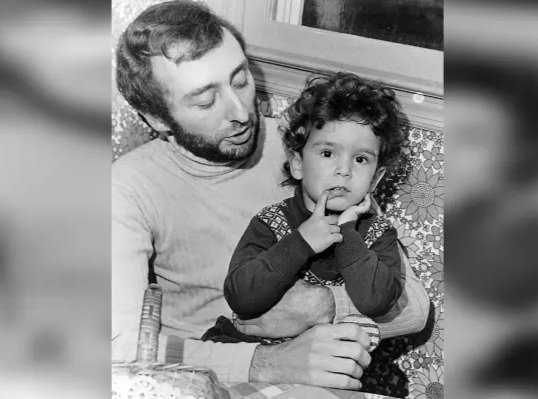

Stephen Wiesenfeld and his son, Jason, in 1975.

Fifty years ago this month, a healthy baby boy was born to Stephen and Paula Wiesenfeld in Edison, NJ. Within hours, however, the celebration of a birth turned into unimaginable tragedy when Paula suffered an amniotic embolism and died on the same day her son was born. It was June 5th, 1972.

Devastated and in the fog of grief, Stephen returned to his home to face the daunting task of raising his son Jason as a single parent. Although the circumstances could have easily been overwhelming for a young father, he found strength in a parent’s instinct to care for his child no matter the circumstances. “I was prepared to take him home and take good care of him,” Stephen recalled later.

As it turns out, that determination to be the best possible parent for his son, led him on an amazing legal journey that involved confronting an archaic statute of federal law. It also led him into a lifelong friendship with perhaps the most iconic female jurist in our country’s history - Ruth Bader Ginsberg.

——

Paula Wiesenfeld had worked as an educator for seven years and was a math teacher at Edison High School at the time of her death. During her employment, she paid, like all teachers, Social Security taxes. As part of his efforts to care for his son, Stephen applied to the Social Security Administration for the same benefits available to widows with children - commonly referred to as the “Mother’s Insurance Benefit.” SSA rules, however, did not allow for a similar benefit to be paid to surviving widowers with children in their care. There was no comparable “Father’s Insurance Benefit.”

Stephen was both frustrated and confused by the rejection of his request for benefits. The potential benefit was a meager $206 per month, but there was a principle involved and Stephen wanted to pursue justice for himself - and for his late wife. “Why was Paula paying money to Social Security? And what happened to the money she paid in?” he asked. So he did what a lot of disgruntled citizens do when they feel they have been treated unjustly - he wrote a letter to the editor of his local paper in November of 1972.

To the editor:

Your article about widowed men last week prompted me to point out a serious inequality in the Social Security Regulations. It has been my misfortune to discover that a male cannot collect Social Security benefits as a woman can. My wife and I assumed reverse roles. She taught for seven years, the last two at Edison High School. She paid maximum dollars into Social Security. Meanwhile, I, for the most part, played homemaker.

Last June she passed away while giving birth to our only child. My son can collect benefits but I, because I am not a WOMAN homemaker, can not receive benefits. Had I been paying into Social Security and, had I died, she would have been able to receive benefits, but male homemakers can not. I wonder if Gloria Steinem knows about this?

Stephen Wiesenfeld

Edison

“I wrote the letter … because I was looking for somebody to give me some direction and to point out this inequity in the law,” recalls Stephen. As fate would have it, somebody did learn of the letter - and she turned out to be perhaps the most qualified person in the country to help him pursue his quest for equal treatment under the law.

——-

Ruth Bader Ginsberg in 1972 when she became the first female tenured professor at Columbia Law School. (Librado Romero/The New York Times)

In 1972, Ruth Bader Ginsburg had just become co-founder of the Women’s Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union. A brilliant legal mind, she had suffered gender discrimination early in her career and had difficulty finding employment despite having spent two years at Harvard Law and later graduating from Columbia Law at the top of her class. When she matriculated at Harvard in 1956, she was one of nine women in a class of 500 students. It is reported that the dean of the law school met with the nine female students and asked, “Why are you at Harvard Law School, taking the place of a man?”

After meeting with Stephen to discuss his case, RBG ascertained that his case was an excellent opportunity to challenge legal gender-based discrimination. Almost counterintuitively, the strategy of demonstrating gender discrimination against a man was her opportunity to shine a bright light on the types of discrimination routinely faced by women of that era. With Ruth’s counsel, Stephen sued on behalf of himself and similarly situated widowers in 1973. He claimed that the relevant section of the Social Security Act unfairly discriminated on the basis of sex and sought summary judgment. A three-judge panel of the U.S. District Court agreed with his arguments and granted Wiesenfeld’s motion for summary judgment.

The victory in District Court was a critical first step but Ginsberg had her eyes on a much larger judgment that would help reshape the landscape of gender equality throughout the country. She anticipated that the case would be appealed and she was proven correct in that assumption when U.S. Solicitor General, Robert Bork - a lynchpin in the Saturday Night Massacre during the Nixon administration - appealed the decision and took the case straight to the U.S. Supreme Court. Stephen Wiesenfeld was about to find himself on the biggest legal stage in the land.

—-

As Stephen’s case wound its way through the legal system, he was obliged to suppress his income so that he did not exceed an earnings threshold that would have disqualified him from consideration for the Social Security benefit and, in turn, invalidate his legal claim. He essentially needed to voluntarily impoverish himself to keep the case alive.

He quit a promising job and opened a bicycle shop. As the owner of the business, he was able to regulate his earnings in a way that kept him eligible for the social security benefits - or at least eligible if he had been a widow and not a widower. Even RBG was not aware of his decision. “I did not discuss my plan with Ruth or anyone else. I knew no one would agree with me. I was leaving a very lucrative job and a promising future to stay home and raise Jason while receiving a Social Security benefit of just $206 per month. But I was, and still am, very principled. What I was doing to favor equal treatment for men and women, according to law, had reached a new level of importance to me.”

——-

On January 20th, 1975, Stephen found himself in the courtroom of the United States Supreme Court sitting at the plaintiff’s table with Ginsberg. One justice, William Douglas, was ill, so eight male Supreme Court justices listened to the arguments put forth by the diminutive woman with a brilliant legal strategy and a heart for justice. The fact that Stephen was present during the oral arguments was unprecedented for RBG. “She had never before, at the Supreme Court, had her client sit at the table with her,” says Stephen. “I found out later that she wanted the Justices to see a male in front of them and hoped that the all-male Court would identify with me. She wanted the Court to understand that this was reality; that this sort of sex stereotyping hurt many people, everyday people, people like Stephen Wiesenfeld.”

Leaving the court that day, Ginsberg was hopeful that her argument would prevail. She explained to Stephen that even a 4-4 split among the justices would allow the lower court decision to stand. They exchanged pleasantries and Stephen returned home to care for Jason and wait for the decision.

The decision was handed down on March 19th of that year. The court ruled 8-0 in favor of Wiesenfeld. RBG’s bold strategy had worked even better than she hoped and Stephen Wiesenfeld’s surreal saga that was born of a terrible tragedy had resulted in a groundbreaking victory for both Stephen and the progress of gender equality before the law.

A neighbor was the first person to call Stephen after the decision was handed down. Then a local radio station called to get his reaction. The third person to contact him was Ruth Bader Ginsberg calling from a payphone on the side of the highway. That moment signaled the end of their professional association but was just the beginning of a personal friendship that would last for the balance of RBG’s life. “We had a close friendship,” says Stephen. “We knew a lot about each other’s personal lives. We would discuss families and vacations - that kind of stuff. Over almost a 50-year span.”

The Wiesenfeld case further enhanced Ginsberg’s rising national profile and in 1993 she was nominated by President Bill Clinton to be only the second woman to serve on the Supreme Court. The last person to testify on her behalf during the Senate hearings to consider her nomination was an old friend and, as she once said, her “favorite client” - Stephen Wiesenfeld.

Even during her tenure as a Supreme Court justice, RBG maintained her friendship with Stephen. She officiated at the wedding of Jason Wiesenfeld in 1998 and when Stephen remarried in 2014, RBG officiated her friend’s wedding at the Supreme Court. They occasionally got together for dinners and traded correspondence regularly.

——-

Ruth Bader Ginsberg and her husband marty visiting Stephen Wiesenfeld (r) in Asheville.

Stephen never anticipated the national attention that would come his way when he penned that letter to the editor in 1972. But today, he is quick to point out that it was always about the principle and not the money. “It was a responsibility to Paula to make sure that the money she paid into Social Security resulted in a benefit to her family. I was changing my life to advance the women’s movement and to make the money that Paula paid into the system have value.”

Today, Stephen mourns the passing of his famous friend in 2020 but appreciates the opportunities to witness her passion and legal brilliance first-hand. “She believed in the United States Constitution, where in the Preamble it says ‘We the people.’ She considered everybody to be ‘We the people.’ Everybody should be treated equally under the law.”

————

Stephen Wiesenfeld will be the guest speaker at a class entitled “Ruth Bader Ginsberg” offered by the Blue Ridge Center for Lifelong Learning on Thursday, June 16th from 10 am to 12 noon in Room 233 of the Sink Building on the campus of Blue Ridge Community College. He will discuss the details of his landmark case, his lifelong friendship with RGB, and be available to answer questions from attendees.

The class fee is $20 for members and $30 for non-members. Registration and payment for the class will be accepted at the door on the day of the class. Cash or check.

For more information, contact Mary Johnston at hiss.kpr@gmail.com or go to www.brcll.com.